Losing grip – Gaining camber

In logic there is a term called reductio ad absurdum. It is a way of showing that an argument is untrue, by following its implications logically to an absurd conclusion. Any statement that contains universals such as ”always”, ”never” and ”everybody” would be highly likely to be exposed as false by this. However, that is not relevant to this column. What is relevant, is that some things are easier to understand, when taken to their extremes. Like progressive camber, also known as camber gain, for example. So today, we shall use a method popularized by Plato more than two thousand years ago, to better understand rear geometry settings of RC drift cars. Fascinating, isn’t it?

A lot of you readers out there are probably way more familiar with progressive camber than I am, but since I needed to spend some time to explain it to myself, I figure it might be worthwhile dedicating a column to it. In essence I assume that if I have trouble understanding something, I am probably not alone in this. Not very humble, perhaps, but nevertheless.

Camber settings are usually referred to as a single digit number, usually somewhere in the three to seven degree range. Sometimes even more, like in the ”oni kyan” style of extreme camber, 鬼キャン in Japanese. The thing is, that regardless what camber you run, unless your upper and lower links are exactly parallell and of equal length, that camber will change as the suspension cycles. How? Why? Well, to better understand that, lets do a Reductio ad Absurdum. Lots of pictures will follow, to illustrate the concept.

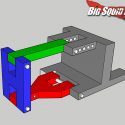

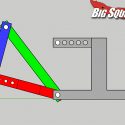

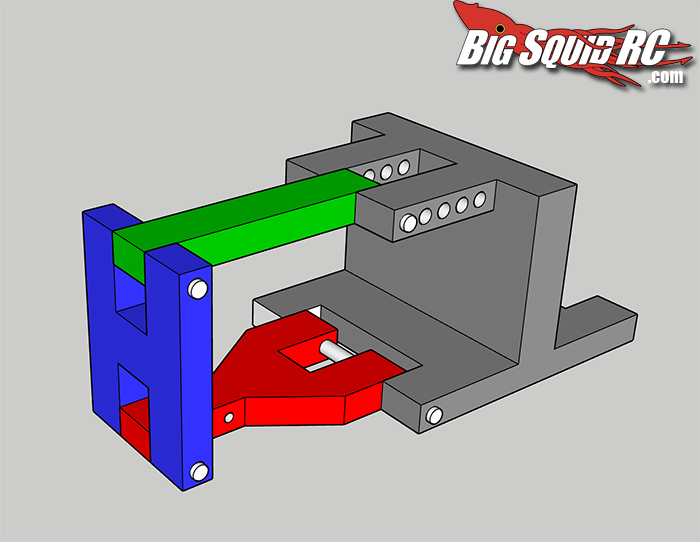

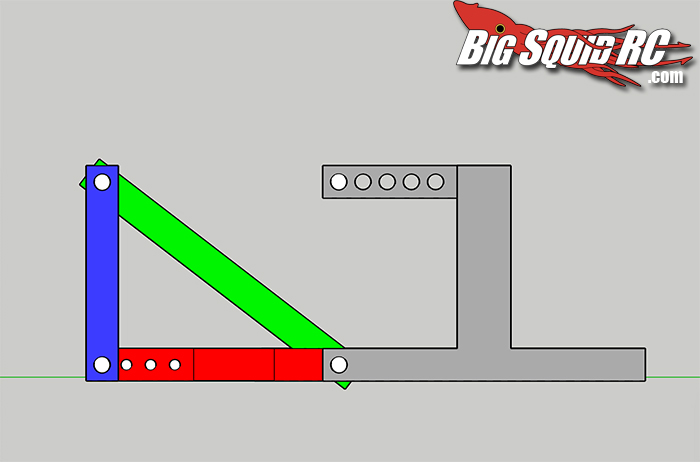

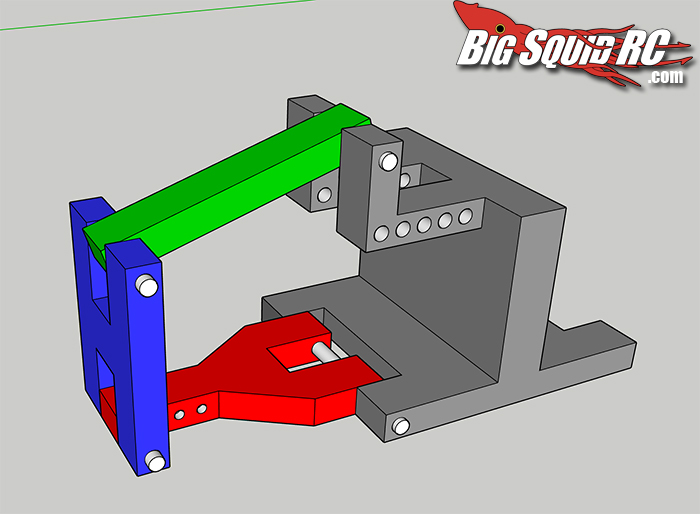

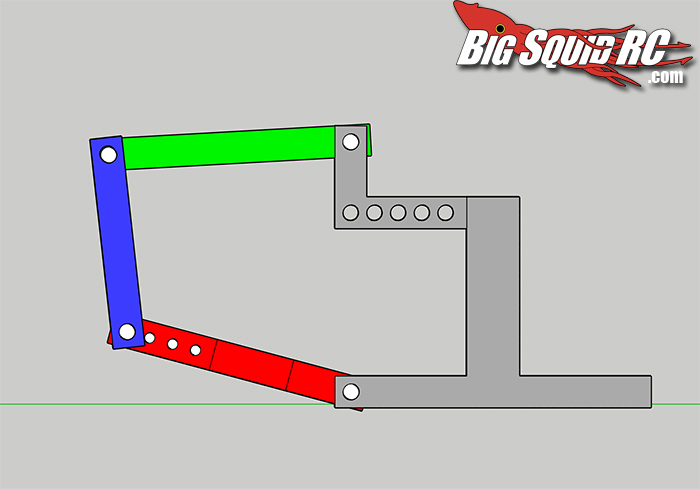

First, let’s have a look at a basic setup, where the A-arm (red) and upper link (green) both are the same length, and mounted between the gearbox (grey) and knuckle (blue) exactly in parallel. I have zero camber, again just to simplify things – the principles stay the same.

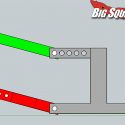

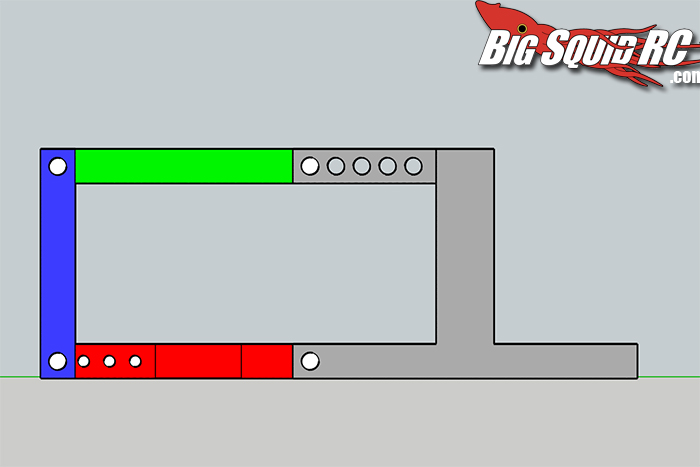

In profile it looks like this:

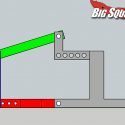

And when we accelerate and compress the suspension, that is, move the A-arm up, the knuckle stays at zero camber. No camber gain at all:

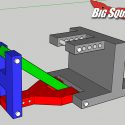

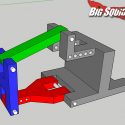

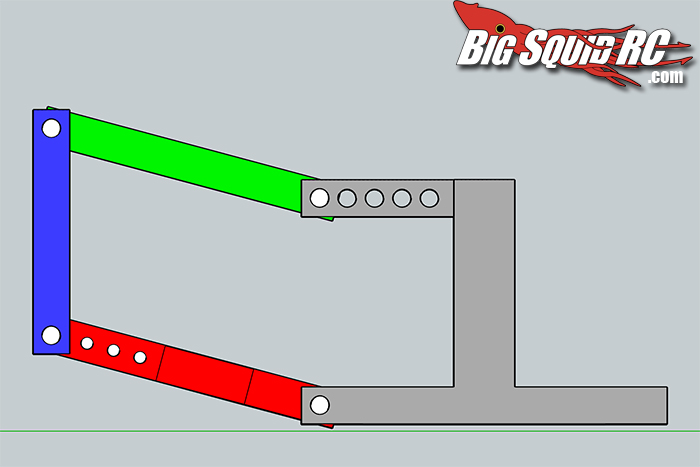

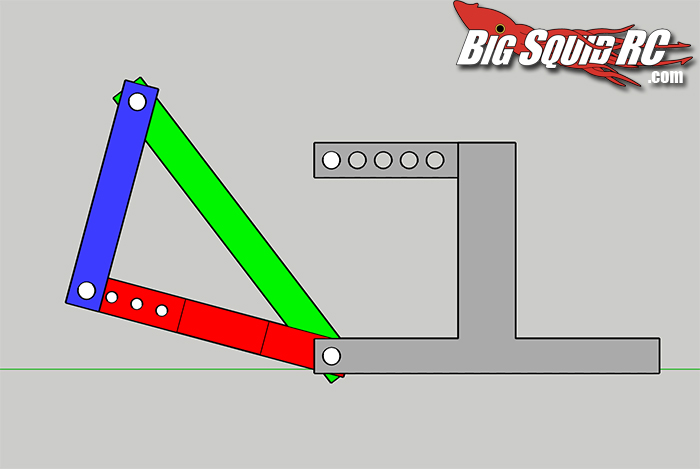

Now lets mount both the upper link and lower A-arms at the same position on the chassis, effectively creating a triangle. Reductio ad absurdum, remember?

When the chassis is pushed down (by acceleration) and suspension compressed, the upper arm will ”pull” the upper part of the knuckle towards itself and negative camber will increase. From neutral camber:

To a lot of camber when suspension is compressed. We have camber gain, or progressive camber, if you prefer that term:

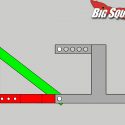

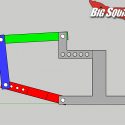

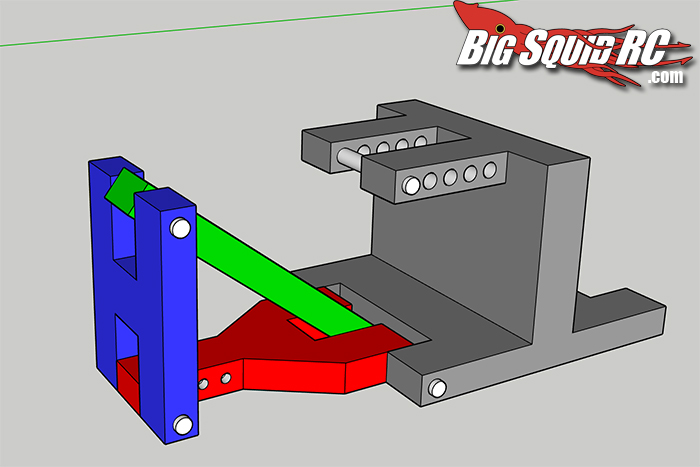

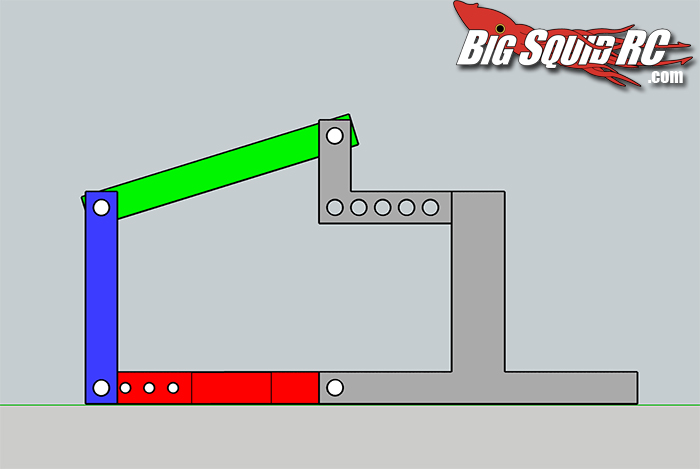

Now, lets do the opposite and see what happens. We mount the upper A-arm way above the lower one. Like this:

Now when we compress the suspension, the upper arm ”pushes” the knuckle away from it. From this:

To this:

In this absurd example, we actually get a bit of positive camber, or negative camber progression, if you will.

What have we learned? That the more angle you have on your upper link (angle as in leaning in towards the chassis), the more camber gain you will have at squat – when the rear of the chassis is pushed down by acceleration, or the front by breaking.

Is this good? I am not to judge, since this depends on what surface you drive on. More camber makes for a smaller contact patch, but whether this also means less grip, depends on the surface you run on. Take a normal eraser, white, formed like a block. Lay it flat on a table surface (large contact patch), and it will proably slide around quite easily. Hold it at an angle, and it will be more prone to sticking. With a block of concrete on tarmac, the opposite would probably be true. The examples might not be great, but the point is simply this: less contact patch does not always equal less grip. This is something you will have to play around with, and see what suits you. Hopefully my explanation has helped you get a better grip on this.

More angle: more camber gain in squat. Less angle: less camber gain.

Of course, things get more complicated than this. A chassis does not only squat, it also rolls. At least if you drift. If you’re into no-prep drag racing, I suppose you don’t turn very much and therefore don’t really need to bother about how chassis roll affects camber gain. And when the chassis rolls, that affects camber progression too, but in a different manner. More on that in another column.

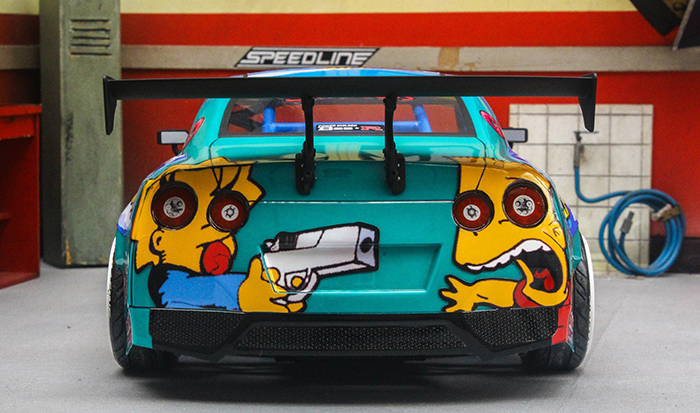

After all this theory, let’s indulge in beauty and finish off with another look at Thirdie’s (of Skunkworks Customs) GT, that was featured briefly a week ago. This Yokomo GReddy R35 SPEC-D body shell sits on top of a Yokomo YD2SX chassis, and was made for a fellow drifter. Who likes Simpsons – who’d have guessed? Lots of work went into it, and Tamiya paints went on it, as well as custom stickers and hand drawn characters in order to make them fit with the rear lights. A work of art.

Beautiful!

Now why don’t you hit the link to read another column?